WHAT IS BARBERSHOP HARMONY?

Sirens competing at the Mid-Atlantic District Northern Division Contest in April 2022

Sirens of Gotham curates a diverse repertoire of a cappella music designed to improve our vocal skills and support the mastery of close-harmony singing by telling a wide range of authentic stories, but we specialize in barbershop harmony.

Barbershop harmony is a style of a cappella music characterized by consonant, four-part chords for every melody note in a predominantly homophonic (the same word sounds at the same time) texture. Barbershop music has a clearly defined tonal center, implied major and minor chords, and “barbershop” (dominant and secondary dominant) seventh chords that often resolve around the circle of fifths, while also making use of other resolutions. A song and its harmonization in a barbershop arrangement are embellished by the arranger to provide support of the song’s theme .

The voice parts in barbershop harmony have different names and functions than those in classical vocal styles. The melody is consistently sung by the Lead, with the Tenor harmonizing above the melody, the Bass singing the lowest harmonizing notes, and the Baritone completing the chord. Occasional brief passages may be sung by fewer than four voice parts. Barbershop singers adjust pitches to achieve perfectly tuned chords (instead of tempered tuning like the piano) in just intonation while remaining true to the established tonal center. Artistic singing in the barbershop style exhibits a fullness or expansion of sound, precise intonation, limited vibrato, and a high level of unity and consistency within the ensemble. When chords lock and achieve full expansion of sound, it is referred to as the barbershop “lock and ring” — achieving this is sometimes called “ringing a chord.”

A BRIEF HISTORY OF BARBERSHOP harmony

The Atlanta University Quartet, Atlanta, Georgia, 1894.

Barbershop music takes its roots from the African-American improvisational traditions of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The instrumental improvisations of early jazz and blues musicians led to vocal harmonic improvisation and vice versa; typical embellishments such as “swipes,” back times, and pickups became ingrained in both forms. “Woodshedding,” or recreationally and improvisationally harmonizing popular music by ear, was popular with Black youth as early as the 1890s, and gave birth to a set of such embellishments and harmony choices with a distinct sound that would later come to form what we think of as the barbershop style.

The Buffalo Bills were the 1950 SPEBSQSA International champions, and became well-known for their portrayal of a barbershop quartet in The Music Man.

You might be familiar with the stereotypical incarnation of Middle American white men in red stripes and straw hats. This stylization developed in the early decades of the 20th century as a vaudevillian reflection of Americana. While dressing in this style is still a nostalgic choice of a few barbershop performers today, contemporary barbershop as a whole is more nuanced and less rigid in genre. The style is now often performed with sophisticated staging, choreography, and theatrical flair, particularly in competitive settings. While many traditional barbershop songs hail from the early 20th century, contemporary barbershop arrangers and ensembles have found ways to apply the same rich harmonic style to many eras and many genres, including musical theater, pop, jazz, and classical. While there are many skilled artists who participate in making barbershop music, and a few who sing barbershop professionally, it is still overwhelmingly an amateur art form — at the heart of barbershop is the simple pleasure of gathering with a community and “the thrill of ringing chords.”

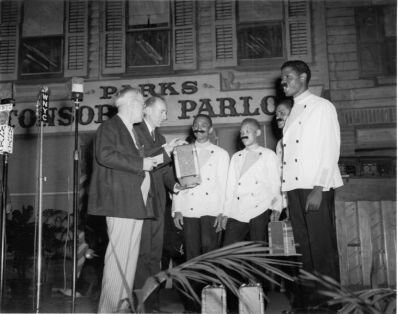

The Grand Central Red Caps win the 7th Annual Barbershop Quartet Contest in Central Park, Manhattan; June 1941.

We would be remiss not to acknowledge that the road by which barbershop music originally entered the American mainstream was plagued with racism. Many early professional quartets were minstrel performers who used blackface and parodied the dialects of their African American counterparts. Their songs often included racist stereotypes and glorified the Old South. Black quartets, despite originating the style, were rarely permitted to record their music and were not given the attention or distribution resources of their white counterparts. Over the course of the early 20th century, as Black barbershop singers were systematically excluded from depictions of the artform, the traditional depiction of a barbershop singer began to be that depiction of the striped-vested, straw-hatted white man. SPEBSQSA (Society for the Preservation and Encouragement of Barbershop Quartet Singing in America), a precursor to today’s Barbershop Harmony Society, regularly promoted the false idea that barbershop music had European origins, excluded black singers from its ranks and from competitions, and celebrated minstrel songs and songs glorifying the Old South. While barbershop is now technically integrated, and songs with roots in minstreldom banned from many competitions, it is still an ongoing journey for the community to combat the effects of such a long period of racism and discrimination.

For a detailed account on the Black roots of barbershop harmony, check out this article and the research it references. Also see the story of the Grand Central Red Caps, a Black quartet that in 1941 became the subject of a fierce debate within SPEBSQSA over the inclusion of Black singers.